Original:

Sold

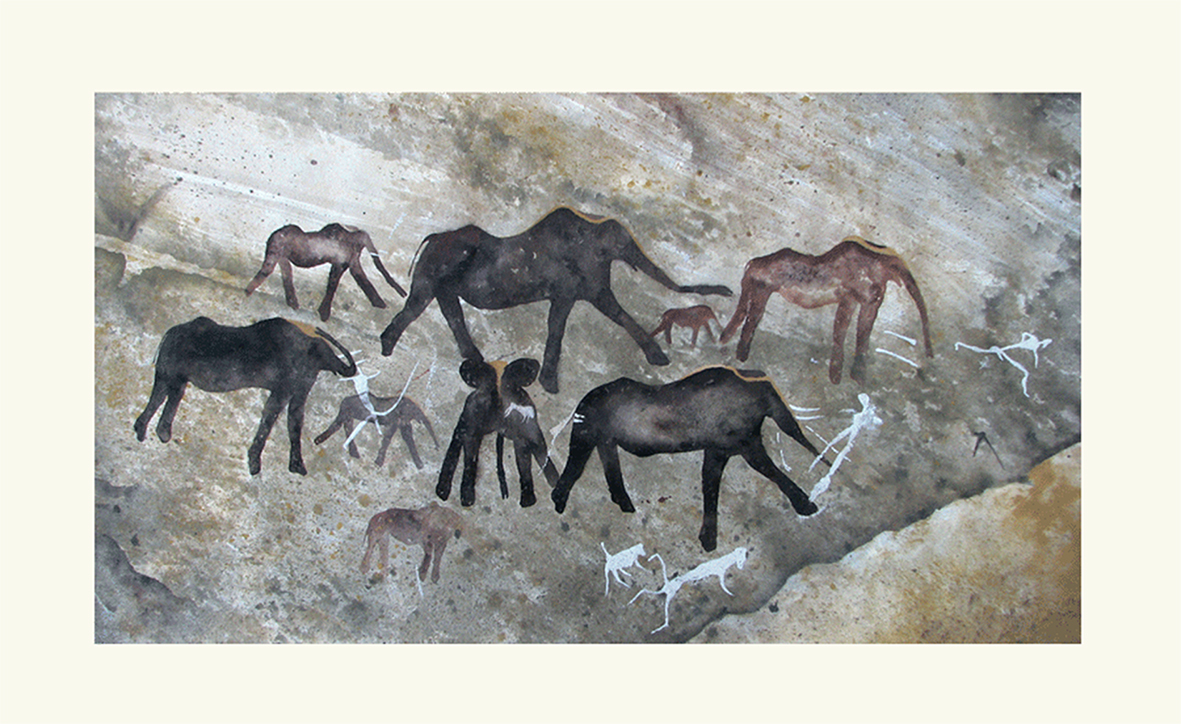

We saw an elephant mother and calf elephant from a painting in the Western Cape. In Plate 24 we appear to have a herd comprising five larger and five smaller elephants. Elephant, like rhebok are commonly painted in family groups. But how do we know that this is a family group? Can we rely on relative size in the art? In this case it is likely that this group of paintings was intended to depict a herd: these animals seem to be the work of a single artist, perhaps in a single sitting. But, in many painted shelters we face a succession of individual paintings, made over many centuries by many different artists. Often the scales are vastly different. There is one site in KwaZulu-Natal, for example, where an

elephant is dwarfed by a much larger painting of a rhebok. We therefore have to be careful of the relative size of animals in large multi-component panels of San rock art. This is also the case with human figures; a few early writers fell into the trap of arguing that larger human figures probably

represented Bantu-speaking farmers whereas small human stick-like figures represented the San. This is demonstrably not the case. Some of the largest human figures depict San ritual specialists transformed in the dance; they have animal hooves and animal heads. But, while therianthropes

are often large, they are not always large. Other potent creatures such as eland, rain-snakes and rain-animals are also often painted very large.

One eland painting in Lesotho is larger than actual life size. Size and potency seem to have some relationship in San rock art, but not all potent things are large.

In this plate the elephant are roughly in the correct proportion in relation to the human figures in the panel. Proportions are one of the ways of tackling the difficult problem of reading relationships in San rock paintings. When images are meant to be read together (as a scene), for example a group of men and women together in a dance, they are usually painted in similar proportions. There may therefore be an interactive and symbolic relationship between the elephants and the human figures in this plate. At least the foremost black elephant seems to have been speared by a human figure. Above, another has white spears beside it. The human associated with the spears is running away, while another below looks as if he is being trampled upon by an elephant. In this context the white animals towards the bottom, just right of centre, become significant. They are baboons. The symbolism of baboons in this region is the subject of a recent thesis by Claire Turner. She argues that baboon characteristics and their painted symbolic contexts make them likely natural models for spirits of the dead. In this case not only do we have baboons, but there are also unusually diagnostic images of spirits of the dead in the

panel immediately to the right of the one we can see here. Some of the shadowy figures amongst the elephants could also be spirits; one of them has a bizarre tail. Spirits of the dead are seen as inherently troublesome in San society. They make people sick and they perform many kinds of mischief. Whatever is captured in this panel, whether rain-making.